Confabulations Introductory Essay

by Allison Schifani

Words are tricky things. If you can call them things.

The collection of Tucker Neel's works presented here get at the slippery non-thingness of language and at its effects on us. His works here offer us text paired with images to which we might suitably assume that text refers. But it is in the jarring gap between the two--the image and the text--that these artworks expose their own power.

We, as viewers, are left grasping at the text and the picture, trying to decipher, trying impossibly to force the text to make sense of the image or the image to make sense of the text. It is in this gap, revealed so cleverly, so sincerely (or perhaps so sarcastically?) by these works that we begin crack open the broader trouble at hand: the subjective experience and the voice of the subject. How precariously these two facets of the social world are linked and how ephemeral, how threatening, how bizarre and uncanny is our experience of this tenuous link.

The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure filled pages of his works (posthumously collected and formed by his students in a Course in General Linguistics) with diagrams--with pictures, trying to show a line between the sound-image (a word, spoken or written) and the concept (the thing itself, supposedly outside of language but to which it refers) to which this sound-image was to get at. What he missed, and what many thinkers have worked to explore, is that the lines he drew and redrew between a word and the concept to which it was connected was just what Neel's works seem to get at--its not such an easy line to draw. It's not a line at all. What lies between signifier and signified is lived experience--bodies, spaces, memories. To get from one side of the diagram to the other is to produce language, a language that communicates something, surely, but invariably something altered by its hearer, by its reader. In getting from the voice to the thing it speaks there are, it turns out, a multiplicity of voices, an infinitude of things.

Images, too, are tricky things. If you can call them things. They, too, are experienced, they are read. And they are always complicated by text. In a country where only the gravest of afflictions and deepest of pains seem immune to ironic mime and sarcasm, it is difficult to tell when--if this was ever possible--someone is saying what they mean. Neel's works seem to hint at this trouble too because, in the end, we're not sure we should take him seriously. By pairing the text with the image, playful, sometimes downright goofy images, we are not left just to wonder at the meaning secured somewhere, unreachably, behind the text, behind the images, but also at ourselves, our own skills at reading.

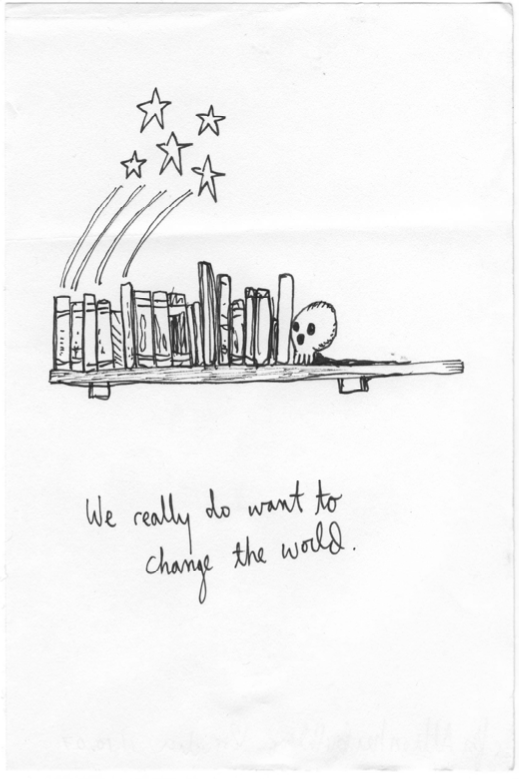

The first work I saw of this collection was given to me at an informal and somewhat raucous art opening in the Eagle Rock neighborhood of Los Angeles. The image was a bookshelf, floating out of context on the white page, atop it a row of books without visible titles--a human skull set up at one side as a book end and at the other, five shooting stars leapt inexplicably up from the books and into space. Below was the inscription, "We really do want to change the world." I wondered, at first, if I had missed the joke. If that 'really' mocked idealism or if that skull exposed the consequences of its inevitable failure.

That piece has been moved about my house for over two months now and, because it's mine, there is no longer a joke to get. I did the job that text requires. I produced my meaning which shifts and stirs and won't sit still. But the eyes of that little skull, the illegible spines of those books, constantly remind me that meanings, like memories, like living, won't sit still either. They have to be made and remade.

Finally, I think, there is the tricky thing (if you can call it a thing) that is joy. Neel's works are jostling, confounding even, but they are always also about a certain amount of play--with language, with image, with the wide open space between the viewer and the work viewed. And this means that these works have a certain political potency. There is always subversive power in play, in pleasure, and in joy. Long histories of political art and activism make that more than clear. If nothing else, Neel gives us a little space to play in. That is no small offering.

-Allison Schifani

©2024 Tucker Neel. All rights reserved.