“Art In The Streets at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles,” ARTPULSE Magazine, Vol. 2 No. 4, Summer 2011.

It’s hard to see MOCA’s blockbuster exhibition, “Art In The Streets,” apart from its surrounding controversies. The show’s problems began back in 2010 when MOCA’s new director and “Art In The Streets” chief curator, Jeffery Deitch, had the artist Blu’s mural of dollar bill-draped coffins on the side of the museum painted over, so as not, according to Deitch, to offend the surrounding community and those who regularly come to commemorate Japanese American veterans at the nearby Go For Broke memorial. Given Blu’s worldwide reputation as a politically engaged artist, and the fact that no one from the community had actually complained about the mural’s content, Deitch’s deletion of the work comes across as directorial and curatorial ineptitude (if his concerns were genuine, he should have stepped in before the mural was completed). For many concerned with MOCA’s future, the entire incident labeled the museum’s new regime as unsupportive of opinionated artistic expression. The mural’s replacement, an undulating scene by Lee Quinones portraying a fractal-emitting railroad train engine soaring over the U.S. Constitution toward a female Native American in a headdress, is so embarrassingly awkward and slapdash as to betray the hastiness of its construction and the anxieties underpinning its role as a secondary ameliorative white-washing, doubling Deitch’s precedent-setting act of censorship.

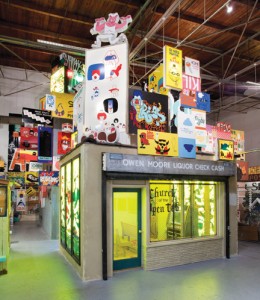

Devin Flynn, Todd James, Josh Lazcano, Barry McGee, Dan Murphy, Stephen Powers and Alexis Ross. Street, 2011. Mixed media (wood, spray paint). Courtesy of the artists. Image courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA). Photo: Brian Forrest

Now that the show is up, MOCA is actively working to paint over any actual unsanctioned street art in the nearby Little Tokyo area, has hired guards to patrol the streets around the museum on bikes, and is using its security cameras to find street artists vandalizing the surrounding property. How does this increased surveillance and the removal of in situ street art frame the creative energy, political and community engagement, and communicative power of art from the streets? Perhaps the most troublesome problem of the exhibition is that the art in “Art In The Streets” is, in fact, not in the streets. So what happens when this art enters MOCA and becomes art in the museum?

One answer to this question comes with Banksy’s crowded installation consisting of life-size figures wearing hazmat suits posed in a post-apocalyptic golf game, as well as a dozen or so paintings, one of a still from The Rodney King beating video, with the brutalized King replaced by a piñata. Unlike how Banksy’s street art communicates out in the real world, where it takes the element of surprise to inspire its audience to rethink power dynamics and question authority, in MOCA this work comes across as tame, an exhibition of the “Banksy style.” Many of the other works in the exhibition fall into the same trap, sterilized by their surroundings. If I came across RETNA’s expansive mural painted on the outside of the MOCA gift show on, say, a stucco wall on Western Ave., I would have no choice but to stop and stare and think about how its Rococo calligraphic intensity intervenes into an otherwise unexceptional pedestrian experience. But in the museum, the piece registers as the simulacra of, rather than a consequential engagement with, a critique of who can put up words and imagery in public.

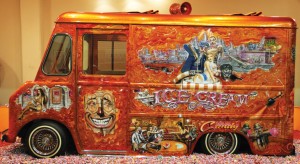

Mister Cartoon, 1963 International Ice Cream Truck, 2010, Urethane enamel candy painted freehand on truck. Photo: Estevan Oriol

One major institutional problem with the exhibition is that it is saturated by heavy-handed sponsorship from the Levi’s and Nike corporations. The multinational clothing and lifestyle brand Levi’s occupies an entire wing of the museum with an interactive video installation, and Nike has a skate park near the entrance that only their corporate-sponsored skateboard team can ride. The two corporations have also executed a near complete takeover of the museum’s gift shop, selling limited edition jackets, shoes, and apparel, donating the proceeds to “the museum and its community programs,” while at the same time saturating the consciousness of their target market consumers. Such in-your-face corporate branding colors all the work in the show. One wonders what Malcom X would think of Shepard Fairey’s use of his likeness to wallpaper the MOCA gift shop, given that, according to a 2011 report released by the U.S. International Textile Garment and Leather Workers’ Federation, Levi’s and Nike are still using subsidiary companies that routinely engage in union-busting and create sweatshop factory conditions around the world. Unfortunately, many visitors to the museum will ignore this hypocrisy, as well as Fairey’s perpetual unauthorized use of grassroots revolutionary imagery, employed without compensating the original artist, to promote his own Obey brand (and likewise the brand of whatever corporation hires him to promote their products), in favor of the visual enchantment his signature graphic formalism has become known for.

Installation view of “Art in the Streets” at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, April 17-August 8, 2011. Photo: Brian Forrest

As it is in the streets, the most successful works in the show successfully construct display strategies that claim their own space, by establishing dedicated viewing environments that don’t just mimic the street, but instead pose alternative realities for viewers to reconsider the very notion of “street art.” In this sense, customized cars by artists like Kenny Scharf and Keith Haring, and a mind-bendingly sumptuous ice cream truck by Mr. Cartoon, festooned with airbrushed scenes, some of them unfortunately highly misogynist, maintain the fresh intensity of their intended location, since, after all, a motor vehicle is still a motor vehicle, even if it’s not on the street.

Additionally, Todd James, Barry McGee, Stephen Powers, Devin Flynn, Josh Lazcano, Dan Murphy, and Alexis Ross’ Street (2011), is a world unto itself, a Disneylandesque, miniaturized urban city block overtaken by ironic posters, considered dedicated wall pieces, surreal installations of body parts holding spray cans, a church festooned with beer cans, and a non-functioning bathroom and attendant wall markings, and all manner of “street art.” This space proposes an alternate universe from what happens outside of the museum, a free-for-all world of decriminalized graffiti, with no mark buffed, no piece removed. Such an over-the-top street art paradise would seem far too idealized, like wishful thinking, were it not for a video installation on the roof of the entire complex playing a brief, looping, comedic advertisement for the fictional, “Style Wars: The Musical,” which features cheesy songs, pirouetting taggers, and a dancing spray can. This video, and its complimentary street scene, self-reflexively critique how the commoditization of street art, its absorption into mainstream corporate culture, might threaten its iconoclastic potential. At the same time, the presentation of this yet-to-come musical skewers the self-congratulatory spectacle that frames the entire exhibition, as if to point out something very present in the exhibition as a whole: the problem of trying to move the energy of Broadway Blvd. indoors.

©2024 Tucker Neel. All rights reserved.