Ask A Design Historian:

How Greco-Roman statues became a design microtrend

by Tucker NeelShaping Design, Oct. 11, 2021

Classical busts seem to be everywhere in design today—that is, once you know to look for them. Lately, they've made appearances in a slew of yearly trend reports including Behance, 99Designs, and Medium. PRINT Mag included them in a round up claiming an 80's design comeback. Where did the trend come from? A reader puts the question to Otis College of Art and Design professor Tucker Neel for answers.

Reader Question: I've been noticing a lot of Greek and Roman sculpture in graphic design like this. What are the origins of the trend?

Today, the use of Greco-Roman busts largely comes from Vaporwave, an electronic music genre that originated in the early 2010’s and the first music genre made entirely by and for an internet audience. Using unlicensed samples from a variety of pop-cultural sources from the 80s and 90s, Vaporave artists spliced together sounds from TV commercials to Muzak, in sampled, looped, and elongated audio clips, producing eerily familiar, yet ominous soundscapes teetering on the edge of catastrophe. (The genre is also subversely political.)

It all goes back to the 2011 release of the album FLORAL SHOPPE (フローラルの専門店, Furōraru no Senmon-ten) by Macintosh Plus (MACプラス) (also known as Vektroid, among other names). The album's cover shows a bust of the Greek God Helios from Ancient Greece’s Hellenistic period on a checkerboard plane, with a pixelated skyline image of the Twin Towers floating in the background. The san serif album title and artist name, both in Japanese, are in dayglo green, making a vividly perfect contrast to the album's fuschia background.

After its release, the Floral Shoppe aesthetic (an eclectic mix of gridded, digital landscapes, early internet iconography, and the occasional Classical statue) became the style for Vaporwave. It's an aesthetic so formulaic there's even a Youtube tutorial on how to make your own. So why are we seeing Greek busts in design today? The short answer is you have the last decade of the Vaporwave aesthetic to thank.

How are we seeing this online right now?

A lot of the more recent uses of marble busts in design use 3D renderings that are then manipulated in one way or another: with gradient and color treatments, duplications, CGI, and even neon lights.

But let's get one thing straight about the ancient artifacts themselves—they were not carved to be white. When the statues were rediscovered during the Italian Renaissance, the pigmentation on these statues had all but disappeared. Artists from the Renaissance period then thought (incorrectly) that was the intention of the original sculptor. And for the most part, they've been portrayed that way ever since.

Where did we see Greco-Roman statues before Vaporwave? What did they symbolize then?

Their meaning really started to take shape after 1764, when Johannes Winckelmann wrote History of The Art of Antiquity, which systematized the early study of art history and suggested that ancient Greek sculpture was the height of artistic achievement against which all others should be judged.

Winckelmann also took the whiteness of Grecian marbles as the intentional work of the ancient artists, equating them with purity and perfection. This reflected the time in which he lived—and a growing white Euroethnic identity. For academics that followed in Winckelmann’s footsteps, these statues became a catch-all symbol of Enlightenment ideals, and a problematic totem to European dominance.

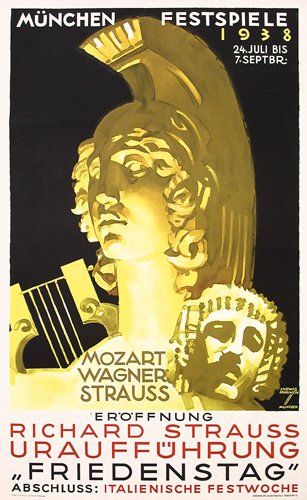

Representations of the “classical ideal" began to appear in new contexts. Wealthy aristocrats who toured the Mediterranean in the late 18th century, as part of what's known as the Grand Tour, began to collect Classical busts and other artifacts as souvenirs. The busts often appeared in the background of aristocratic portraits from that period. About a century and a half later, Germany's Third Reich included fascistic interpretations of Neoclassical statuary and architecture in its propaganda, like Ludwig Hohlwein's 1938 poster for a classical music concert.

Ludwig Hohlwein, poster for a classical music concert, 1938

Rockwell's Man Holding Two Portrait Busts (aka Delivering Two Busts), 1931

Rockwell's Man Holding Two Portrait Busts depicts an exhausted middle-aged deliveryman in a disheveled uniform holding classical marble busts. They are frozen in time, perfect, while he is real, embodied, ephemeral, and imperfect. As Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies Norman Rockwell Museum notes, "This is truly a comparison of the ideal to the real." Painted during the Great Depression, the class critique underlying an image of a tired worker lugging the baubles of the upper class wouldn’t have been lost on Saturday Evening Post readers.

Nothing is designed in a vacuum. Hopefully this helps bring the current use of the marble statue—and its controversial use throughout history—to light.

©2024 Tucker Neel. All rights reserved.