Guest Editor Letter for Artillery Queered

by Tucker NeelArtillery Magazine, May/June 2011. Vol. 5 Issue 5

Dear Reader,

What makes something “queer”? If we go to Webster we see that, in the main, the word means to differ from what is normal. When it comes to discussing artworks, this word brings with it a wealth of academic thought and a trove of exciting art production that expands this definition and the power of queer as a verb, something beyond a slur, something that de-stabilizes the of binary oppositions separating one identity from another. Queering throws the whole order of things into flux. It agitates, and often erases the imaginary lines demarcating female from male, gay from straight, masculine from feminine, submissive from dominant. It is liberating. For me, the actor, performer, singer and artist Divine is one of the greatest works of art to ever grace this earth – and one of the queerest. Divine embodies something totally abnormal yet completely self-assured: an obese drag queen sporting loud tight clothes and intentionally scary makeup, doing things one is just not supposed to do – from stealing meat in between her thighs from grocery stores, to having sex with her son, to eating shit. That she did all of this and so much more without the tiniest hint of guilt is what makes her queer. Her importance as a queer star is due in no small part to John Waters, who I’m so excited is interviewed in this issue. Waters himself is also an important queer icon, after all the man has made a career out of elevating the discarded and repulsive to the highest art.

As Robert Summers, one of the contributors to this issue, notes in his observant essay on queer interrogations of abstract expressionism, queering can be a very bodily act, often involving a performative action, a body that tweaks, and then contaminates the dominant narrative of how things are “supposed to be.” After reading his essay you won’t be able to think of the “expressivity” of abstract expressionism the same way again.

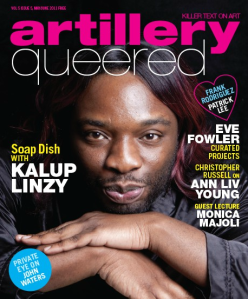

Greg Walloch’s interview with the artist Kalup Linzy also touches on this idea of queer performances by introducing this important artist and his work. Linzy makes some of the most engaging critiques of American melodrama, from old-fashion stage shows to current Soap Operas. In this interview Linzy talks candidly about how his work investigates understandings of race, gender, and sexuality, while ruminating on the artists and thinkers who have influenced his work, one of whom is the great John Waters.

I am so excited to have Monica Majoli as our guest lecturer. Majoli’s practice is an inspiration. Her work engages with subject matter some would find uncomfortable, like bondage, sex toys, and multiple-partner sex acts. For this issue Monica presents two haunting works from her newer series portraying lovers as seen through a black mirror, with images that are both intimate and distant, personal subjects in a very public venue.

When I asked Eve Fowler to curate for this issue, I had no doubt she would select work complicating the idea of a queer Artillery. She did not disappoint. Her selections ask many questions of queerness and abstraction. When we know that the artist is queer, does this influence the production of the work and our understanding of it? Does the framing of the work within the context of this particular magazine issue queer it? Or vice versa?

Frank Rodriguez’s interview with the artist Patrick Lee, who also happens to be his husband, continues this queering of the magazine. We don’t normally think of art writers interviewing their partners because such writing comes too close to “a conflict of interest.” But this intimacy between critic and an artist allows Rodriguez access to a particular understanding of Lee’s art, putting their relationship front and center, producing a text that blurs the boundaries between professional and personal, artist and writer, husband and subject.

There are so many artists making work that can be understood as “queer,” and unfortunately the pages of Artillery can only hold a very small selection. I wish we had many more pages to more fully explore the ways gender, race, class, geographic location, and age influence queer approaches to making art. Though I think many of these positions are touched upon in this issue, it’s obvious that more can always be done. Thankfully, it’s this isn’t the first time Artillery has featured queer art, and it absolutely wont be the last.

It has been a great pleasure and a true honor to work with all the contributors and artists in this issue. Through reading their work, seeing art I was previously unfamiliar with, and discussing the strange and shifting idea of queering Artillery, I have learned a tremendous amount and for this I am truly thankful. It’s nearing the end of this brief editorial gig and I feel I am only left with more questions, more frustrations, and more contradictions. But if trying to queer this magazine has taught me anything, it’s that creating something that frustrates, resists easy interpretation, something that seeks to confound previously solid definitions, is an extremely necessary endeavor.

-Tucker Neel

©2024 Tucker Neel. All rights reserved.