“Nancy Chunn the Otis College Ben Maltz Gallery,” ISM Magazine March, 2008

“Nancy Chunn the Otis College Ben Maltz Gallery,” ISM Magazine March, 2008

Nancy Chunn is a self-described political junkie. Her most recent show, Media Madness, at Otis College of Art and Design, attests to her addiction to the news, an addiction that seems to suit her well. While she doesn’t take revenge on the news media per se, Chunn acts more like a sieve, distilling current events into a personal lexicon of images, signs and symbols to make maps, diagrams, and hieroglyphs that express her fears, frustrations, humor and anxieties.

Chunn is best known for Front Pages, a body of work from January 1- December 31, 1997. During this year she drew on the front page of each day’s New York Times newspaper with bright pastels, adding her own images over photographs, obscuring headlines and sometimes entire stories with expanses of color and carefully chosen texts. Media Madness presents the viewer with two months, June and July, arranged as if they were days on a calendar displaced onto the gallery wall.

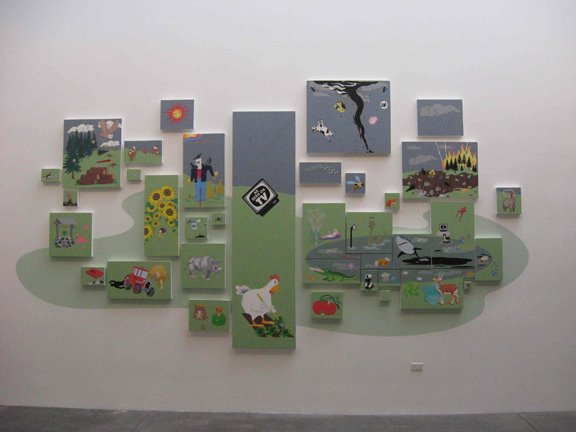

Installation shot of Chunn's Chicken Little and the Culture of Fear

Installation shot of Chunn's Chicken Little and the Culture of FearChunn’s interventions champion her own subjectivity with quips and witticisms and comic-book-like images that bring out the humor, sadness, or ambivalence she feels in relation to the stories in the paper. So a story on, say, an I.R.A. bombing in a British city, condenses into “UP TO THEIR OLD TRICKS” (written in green of course) above two explosions. By whittling the daily news into one-liners, easily digestible combinations of images and text, she replicates the corporate media’s habit of substituting surface for substance, producing sound bites instead of informed analysis, talking points enslaved to the constraints of a scrolling news ticker.

Whether the viewer agrees with Chunn’s summation of the daily news is beside the point. The work is wholly about one woman’s act of reading and reflecting over the course of a year. The artist is the sole locus for the work so impartiality flies out the window. Here we see how the news acts on and through a person. In this way her work performs entirely differently from conventional news media, which relies on the myth of objectivity to maintain credibility.

In addition to revisiting Chunn’s seminal work, Media Madness also includes Chicken Little and the Culture of Fear. Consisting of a suite of four different installations of dozens of small and large canvases arranged on the gallery wall in an expansive salon style, the work tells the story of Chicken Little, a worrisome fowl beset by seemingly endless obstacles and hazards, from falling televisions to homicidal tractors, bimbos in Broncos, and invasive CIA agents. While the work turns many current political, environmental and social issues into a fable with no resolution, Chunn has said that when she completes the last group of paintings she’ll eventually have Chicken Little working for Fox News, a fitting end to a story about fear mongering in the new millennium.

The images of burning forests, toxic waste, genetically modified food and over-consumption in Chicken Little and the Culture of Fear may just be fleeting glimpses of a world temporarily out of balance, or images of an entrenched uber-capitalism that generates countless injustices and neglected catastrophes. Perhaps the saddest thing of all, and what gives Chunn’s work legs, is that the symbols and icons imbedded in her work will outlive the immediacy, the context, of their creation.

This observation came to the fore in her Four Seasons painting series. Utilizing Chunn’s familiar stock of symbols first developed in the Front Pages series, the paintings depict major news stories that occurred during each of the four seasons in 1999. But if it weren’t for the didactic wall text explaining the subjects of each work, one could easily see these paintings as contemporaneous with today’s breaking news. In this way they are history paintings, their subjects specific, yet enduring.

In Spring Cleaning (Spring 1999) the flat, angular images of fallen bodies, fighter jets, armed soldiers, and explosions meant to reference the violence of the Columbine school shootings and the war in Kosovo immediately bring to mind the dead bodies and battle fields associated with the seemingly endless wars America fights either directly or by proxy all over the world today. The message in the work may be rooted in a specific time and place, but the larger polemic is not necessarily historically constitutive. As long as war and violence are part of our everyday life, these pictographs of crumbling buildings, troop formations, bombs, funerals, guns and dollar signs will have lasting resonance.

Looking at Scandal (Winter 1998-99), emblazoned with Day-Glo images of sperm, moist red lips, a giant unzipping zipper and a garbage can stuffed with money and a copy of the Star Report, one cannot help but think of the Bill Clinton/Monica Lewinski muckraking that inspired this flamboyant painting. Yet the toilet at the center, the accusing fingers, computer, and the bald headed man exclaiming”Oops,” also immediately calls to mind the many right wing politicos recently outed for their less-than-hetero behavior. While the story in the painting is from a bygone era, its sentiment is symbolically perennial: We seem to be more interested in who politicians fuck than who they fuck over.

Perhaps this is the larger message imbedded in Chunn’s work, that we should use the news as a vehicle for developing our own symbolic, and perhaps radical responses. Registering dissatisfaction is a first step but we need to go beyond critiquing the news to actually making the news. Now that the time for action has come the pressing question is how do we, as cultural producers, change the game, rewrite the rules and shift the power structure in such a way that the images displayed in Chunn’s work are no longer up-to-date, but instead vestiges of an embarrassing yet distant past?

©2024 Tucker Neel. All rights reserved.