Permissions: Linda Besemer, Diana DeAugustine, Sherin Guirguis, Olga Koumoundouros,

by Tucker NeelHighways Gallery, 18th Street Arts Complex, Santa Monica, CA 2010

A few months back I was asked by Marcie Begleiter to organize an exhibition about the legacy of the artist Eva Hesse to coincide with the play Meditations: Eva Hesse, which she had recently finished writing. It was a rather open-ended prompt. I have always been interested in Hesse’s work, ever since I encountered her odd sculptures in The Hirshhorn Museum and The National Gallery of Art in DC where I grew up. Her work seems to be all about embracing the communicative potential of an awkward sculptural slouch, a logical yet incomprehensible gesture, something that calls into question all verifiable “truths.” So I was happy to accept the invitation to curate, excited by the possibilities this exhibition poses.

Nearly every artist I talked to mentioned, in one way or another, that they not only appreciate Hesse’s work and recognize her importance as one of those artists who changed the game in art history, but also that Hesse holds a special place as a liberating force in their practice. This sentiment applied to many artists, from varying generations, working in multiple media. Why does Hesse hold such an important role in these artist’s respective practices?

Hesse is a transitional and transformative figure in art history. She is heralded as an artist who helped rework Minimalist discourses surrounding the solidity of forms in space. She injected into this previously rigid ism quizzical and often absurd objects with forms alluding to, but never illustrating, subjective realities, body parts and physical states of being. Her work is often fragile, constructed out of fugitive materials like latex and fiberglass and she embraced this impermanence as an important subject. The physical experience of seeing her work still brings forth a sense of bodily awareness in the viewer. In many ways she humanized Minimalist practices and made them more immediately physically resonant.

Hesse was a strong person and an even stronger artist, working with unyielding dedication to her practice even during the last few years of her life when she was battling brain cancer. As a woman working in the American art world of the mid 20th century, a world dominated by men, many of them very macho men, Hesse’s practice can also be seen as important to the rise of feminist scholarship and the increased visability and representation of women artists in the contemporary art world. Women artists today can take inspiration from her resilience and steadfast belief in her own practice.

Against this understanding of Hesse’s well-documented contributions to the shifting discourse defining minimalist and post-minimalist art history, one artist summed up what I was beginning to realize,

“Eva Hesse gave permission to every artist who came after her. She opened the field.”

I concurred and consequentially became interested in what it means for an artist to claim permission from someone long since past. In selecting the works for this exhibition I was interested not just in how these artists use Hesse as a model. In fact, I consciously avoided selecting work that would easily quote from Hesse’s well-known oeuvre. Instead, I endeavored to bring together works that come from a place that has internalized Hesse’s legacy but is not beholden to it in any mimetic sense. Instead I have attempted to present work that does not necessarily look anything like Hesse’s, but in some way updates, complicates, or resituates the discussions she helped originate over thirty years ago.

While in the gallery it’s hard not to start making make one-to-one comparisons with Hesse’s work. This is no doubt because to mention an artist like Hesse in the context of any art exhibition immediately inspires one to speak of material, formal, and perhaps conceptual similarities. One can surely see Hesse's interest in breaking free of the constraints of the field of the canvas (drooping objects onto the floor, away from the wall) in Linda Besemer's work, which does away with the canvas, with a conventional support structure entirely, displaying a painting made entirely out of paint. With her work Besemer questions the predetermined structure and strictures of abstract painting, how we invest ideologically constructed importance in the binary oppositions of front and back, canvas and paint, form and content. By consciously producing work that seeks to dismantle the bulwarks that maintain these binaries, Besemer by extension encourages us to break apart the supposedly unshakable ideological structures that inform other aspects of culture. In this way her work also continues Hesse’s own use of materials and methods that resist simple analysis.

With Sherin Guirguis' work, one may draw parallels to Hesse's embrace of chance irregularities, her ability to heighten the personal or subjective possibilities latent in processes of Minimalist repetition. For example, Hesse’s many ink washes of fields of circular forms against grey or blackened backgrounds bear an oblique resemblance to Guirguis’ works on paper. In the same way, Guirguis’ practice of cutting away at her images, in this instance employing the decorative patterning of Arabic design used in mashribiya screens to delineate the form of an atomic blast against a field of expressive watercolor washes, brings to mind some of Hesse’s early paintings from the mid 1960s, with their protrusions and punctures, bright colors, and strangely suggestive and irregular forms. With both Hesse and Guirguis, the signs of personal or subjective states, references to private parts and private spaces, intermingle with conventional formal structures to compel the viewer to create meaning between these two previously incongruous reference points.

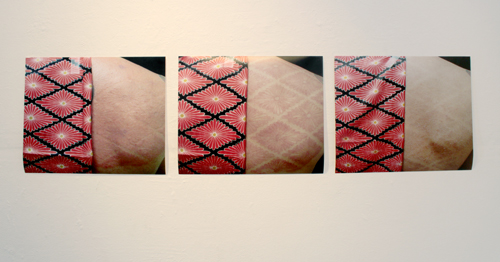

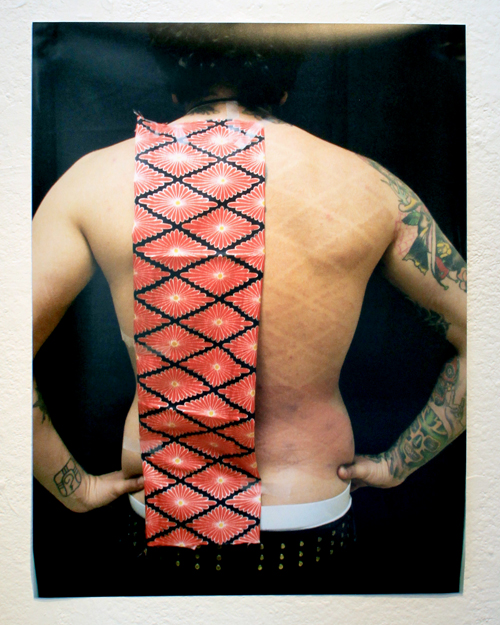

Diana DeAugustine’s striking photographs documenting the healing process of a large ephemeral tattoo evoke associations with Hesse’s own use of patterning, her embrace of things that fall apart, degrade, and change their form with time. De Augustine’s work also resonates against Hesse’s continual interest in making work with inexplicit references to the human body. DeAugustine’s ephemeral tattoos involve a process of puncturing the topmost layer of skin with water instead of ink. The result is a temporary mark where the pigment of the tattoo comes from the blood of the tattooed person, making the mark a kind of exquisite bruise. For the work in this exhibition, DeAugustine created an ephemeral tattoo that continues the pattern of a Japanese Kimono swatch. The photographs show the healing process, skin moving from swollen to flakey, with the design in question emerging and disappearing as well. The photos bring to mind Hesse’s own use of hand-drawn patterning and grid-like geometric forms in drawings from the mid 1960s. DeAugustine’s photos also cause one to recall Hesse’s signature employment of materials with skin-like qualities, like yellowing latex, polyester resin, or translucent fiberglass. Finally De Augustine’s work, like Hesse’s employs the passage of time, the transformation of one formal proposition into another, ghost-like form, a trace or otherworldly version of its previous self.

Olga Koumoundouros’ sculpture also raises questions about the human body, specifically issues of food, consumption, and nourishment. Her sculpture is a pillar of objects used to hold food: a milk jug, a cereal box, an egg carton, a grape container, an aluminum can. Koumoundouros’ previously discarded objects are reinvested with new meaning when she covers them with paper mache’ ads from newspapers, sourced from the free weekly mailers. This transformation calls attention to how physical consumption is tied to both to advertizing and purchasing power, how daily sustenance always involves questions of who has access to resources, whose survival teeters on the brink. The entire totem-like configuration is topped with a piece of electrical conduit salvaged from a home renovation project, which juts out like a conspicuous indexical signpost, pointing to a world outside of the piece - a conduit in search of power. The work has an awkward absurdity to it, accentuated by its tilting pose and weird protrusions. While it is quite stable, it looks as if it could topple at any moment, which consequentially makes the viewer aware of his or her own body in relation to the piece. This work may remind one of Hesse’s repeated use of paper mache' as a medium with great potential for experimentation, a skin to cover phallic or bulbous forms, creating works with great bodily resonance. Koumoundouros’s use of overlooked or everyday items also raises connections Hesse’s employment of unexpected materials in her works, like rope, paper mache', latex and fiberglass. And of course both artists share an interest in indirect references to human bodies.

While the inclination to draw formal and conceptual connections between Hesse’s work and the work in the gallery does provide an interesting framework for seeing the past manifest in the present, it should in no way allow one to view the works on display as derivations of Hesse’s work. These are not imitators. The artists in this gallery make work that only tangentially touches on the look of Hesse’s famous works. In fact, the works here probably have more in common with each other than with Hesse’s. This is not an accident. My intention with selecting the works in this exhibition was to provide a conceptual sounding board for passing references to Eva Hesse, but also to propose a situation where thoughts about Eva Hesse are complicated and enriched with a discussion about what it means to make art today. In some way this exhibition attempts to question the very notion that one can organize a show about the influence of an artist from the past.

This brings us back to the title of the show. Why call this exhibition Permissions? Who is giving permission, and who is accepting it?

The term “permission” here does not necessarily refer to the verbal authorization of, say, a parent granting permission for their child to leave the kitchen table. Instead, the permissiveness at hand is much more aligned to notions of encouragement and motivation, the liberating ability to free ones production of constraints. The “permission” at work here was never sought by the artists present; it was chosen. Permission, in this context, is not necessarily an utterance grounded in the here and now, amongst ones peers or living colleagues. Instead it’s a permission passed across generations and time, something that one has to claim from a person in the past. It’s tied to the notion of finding role-models, heroes and inspirational voices from historically distant sources to justify and support one’s avant-garde present day interests. So to say that Eva Hesse gave permission to artists today means much more than the idea that she “sanctioned” or “authorized” certain forms through her practice. Instead it means that the force of her work, its ability to inspire, inform, and influence artists, is so powerful that artists are still willfully picking her up as someone whose practice enlivens theirs. This is what makes an artist like Hesse timeless, enabling her to reemerge with each successive generation.

©2024 Tucker Neel. All rights reserved.