QUEER EVERYTHING. We May Never Look at Portraiture THE SAME (SEX) AGAIN

by Tucker Neel

Artillery Magazine, March / April 2011, Vol. 5, Issue 4, 56-58.

As the first exhibition housed in a Smithsonian museum to focus solely on sexuality as an important factor in the development of American identity, The National Portrait Gallery’s Hide/Seek Difference and Desire in American Portraiture is a watershed event for art and history. Through portraiture in the form of painting, photography, video, print, installation, and sculpture, this exhibit sheds light on how same-sex desire informs the construction of American identity, asserting that any reading of portraiture can no longer be seen through a strictly heterosexual lens. There’s no doubt that most future conversations about this exhibition will focus on how Wayne Clough, the Secretary of The Smithsonian Institution, spinelessly capitulated to right-wing pressure and censored David Wojnarowicz’s video A Fire in My Belly (1986-87), removing it from the show and sparking vocal protests from artists and activists around the world. Outside of the controversy it generated, Hide/Seek has even more to say about who we are as a nation, and more importantly, how we can see the trajectory of American history through more inclusive eyes.

The best way to understand the impact of Hide/Seek is to look at the many visitor comment books the show generated. The comment book I saw when I visited the museum in late December, 2010 had been out for only a few weeks, but it was nearly full with astute analysis of the Wojnarowicz censorship, feedback on specific works in the show, calls for more women and artists of color to be included in the exhibition, observations connecting the exhibition to Don’t Ask Don’t Tell and The Defense of Marriage Act, heart-felt testimonials about coming out and losing loved ones, as well as calls for Clough to resign. The National Portrait gallery should transcribe and reproduce these first-hand observations (perhaps with names and emails redacted) in a book and online as a way to highlight how the show actually impacted its visitors.

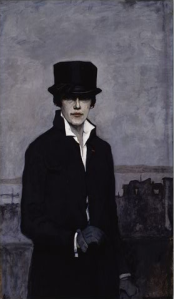

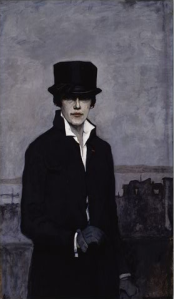

Romaine Brooks, Self-Portrait, 1923

While work in Hide/Seek made before the civil rights movement is over-populated by white male artists, the excellent wall text and book accompanying the exhibition admits to the problematic nature of this imbalance, pointing out that the freedom to be visible, to publicly express desire for the same sex, is complicated by race as well as economic and social positions. One work used to illustrate this point is a self-portrait from 1923 by Romaine Brooks, an artist of considerable means. Dressed characteristically masculine clothes for her time, her face cloaked in shadow, she stands on a balcony against a grey cityscape. The text accompanying the piece inform readers that Brooks‘ status as a wealthy white woman allowed her to live her life more openly than if she occupied a position of less privilege.

Jasper Johns, In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, 1961

In many ways Hide/Seek “outs” important figures from art history, from Walt Whitman to Betty Parsons, Gertrude Stein to Marsden Hartley, Agnes Martin to Annie Leibovitz. For example, one gallery pairs the works of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns together, with wall text clearly stating the fact that the two were once lovers, investigating the impact this relationship had on their work. The show asks if their break up influenced John’s In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, a large brooding grey painting from 1961, its title a reference to one of O’Hara’s poems about lost love. While for many “in the know” the sexual preferences of all these artists are old news, the fact is that the omnipresence of heteronormative curatorial strategies in most museums promotes the assumption of heterosexuality in both the artist and the subject of work, unless explicitly stated otherwise. Hide/Seek upends this supposition, placing same-sex desire front and center, considers it an important factor in understanding the work on display.

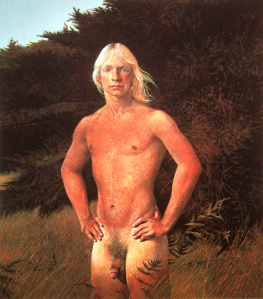

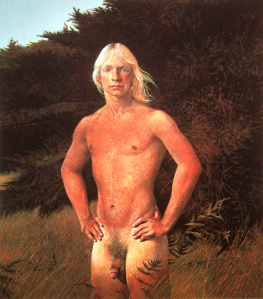

Andrew Wyeth, "The Clearing" 1979

Equally important is the way the exhibition proposes new readings of established artists’ works. For example, in The Clearing by Andrew Wyeth from 1979, we see a muscular, tan, and nude man standing in knee-high grass, his blonde hair rustled by a breeze, his tan line stopping just above his crotch. It’s a startling image, both because it depicts a naked man, and because it’s painted by such a well-known artist, interrupting the supposed heterosexual solidity of his oeuvre. The exhibition does not claim Wyeth to be a homosexual, but it doesn’t state that he isn’t. One could see this as “guilt by association,” but only if you want to narrow your understanding of desire. Hide/Seek is as much about art as it is about artists, and one of the greatest points the show makes is that “straight” artists can, and often do, create works that queer people find reflect their own desires.

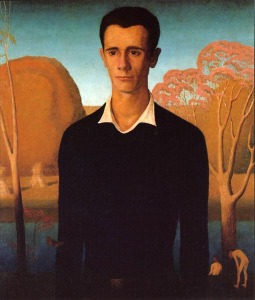

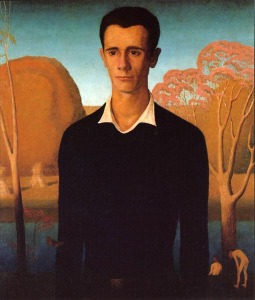

Grant Wood, Arnold Comes of Age, 1930

This happens again in Grant Wood’s Arnold Comes of Age, a painting from 1930 of a slight young man staring into the distance against a fall landscape. In any other exhibition the image might be understood as one of Wood’s signature depictions of traditional America, were it not for the nude boys bathing in the corner of the portrait. In Hide/Seek the image takes on a narrative that embraces, rather than represses the possibility of same-sex desire. Additionally, the exhibition positions this desire as part of an entirely healthy personality, a welcome contrast to the many ways American culture has constructed the image of queers as morally broken and psychologically ill.

Annie Leibovitz, Ellen DeGeneres, Kauai, Hawai, 1998

This exhibition has the possibility of changing the way one views everything else in the museum, from the Elvis at 21 exhibition around the corner, to The Struggle For Justice exhibition, not coincidentally next door, which highlights people who played an important role in the history of American civil rights. Hide/Seek holds the potential to queer everything, from the Norman Rockwell show downstairs, to exhibitions at other museums on The Mall, and institutions beyond the Nation’s Capital.

by Tucker Neel

Artillery Magazine, March / April 2011, Vol. 5, Issue 4, 56-58.

As the first exhibition housed in a Smithsonian museum to focus solely on sexuality as an important factor in the development of American identity, The National Portrait Gallery’s Hide/Seek Difference and Desire in American Portraiture is a watershed event for art and history. Through portraiture in the form of painting, photography, video, print, installation, and sculpture, this exhibit sheds light on how same-sex desire informs the construction of American identity, asserting that any reading of portraiture can no longer be seen through a strictly heterosexual lens. There’s no doubt that most future conversations about this exhibition will focus on how Wayne Clough, the Secretary of The Smithsonian Institution, spinelessly capitulated to right-wing pressure and censored David Wojnarowicz’s video A Fire in My Belly (1986-87), removing it from the show and sparking vocal protests from artists and activists around the world. Outside of the controversy it generated, Hide/Seek has even more to say about who we are as a nation, and more importantly, how we can see the trajectory of American history through more inclusive eyes.

The best way to understand the impact of Hide/Seek is to look at the many visitor comment books the show generated. The comment book I saw when I visited the museum in late December, 2010 had been out for only a few weeks, but it was nearly full with astute analysis of the Wojnarowicz censorship, feedback on specific works in the show, calls for more women and artists of color to be included in the exhibition, observations connecting the exhibition to Don’t Ask Don’t Tell and The Defense of Marriage Act, heart-felt testimonials about coming out and losing loved ones, as well as calls for Clough to resign. The National Portrait gallery should transcribe and reproduce these first-hand observations (perhaps with names and emails redacted) in a book and online as a way to highlight how the show actually impacted its visitors.

Romaine Brooks, Self-Portrait, 1923

While work in Hide/Seek made before the civil rights movement is over-populated by white male artists, the excellent wall text and book accompanying the exhibition admits to the problematic nature of this imbalance, pointing out that the freedom to be visible, to publicly express desire for the same sex, is complicated by race as well as economic and social positions. One work used to illustrate this point is a self-portrait from 1923 by Romaine Brooks, an artist of considerable means. Dressed characteristically masculine clothes for her time, her face cloaked in shadow, she stands on a balcony against a grey cityscape. The text accompanying the piece inform readers that Brooks‘ status as a wealthy white woman allowed her to live her life more openly than if she occupied a position of less privilege.

Jasper Johns, In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, 1961

In many ways Hide/Seek “outs” important figures from art history, from Walt Whitman to Betty Parsons, Gertrude Stein to Marsden Hartley, Agnes Martin to Annie Leibovitz. For example, one gallery pairs the works of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns together, with wall text clearly stating the fact that the two were once lovers, investigating the impact this relationship had on their work. The show asks if their break up influenced John’s In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, a large brooding grey painting from 1961, its title a reference to one of O’Hara’s poems about lost love. While for many “in the know” the sexual preferences of all these artists are old news, the fact is that the omnipresence of heteronormative curatorial strategies in most museums promotes the assumption of heterosexuality in both the artist and the subject of work, unless explicitly stated otherwise. Hide/Seek upends this supposition, placing same-sex desire front and center, considers it an important factor in understanding the work on display.

Andrew Wyeth, "The Clearing" 1979

Equally important is the way the exhibition proposes new readings of established artists’ works. For example, in The Clearing by Andrew Wyeth from 1979, we see a muscular, tan, and nude man standing in knee-high grass, his blonde hair rustled by a breeze, his tan line stopping just above his crotch. It’s a startling image, both because it depicts a naked man, and because it’s painted by such a well-known artist, interrupting the supposed heterosexual solidity of his oeuvre. The exhibition does not claim Wyeth to be a homosexual, but it doesn’t state that he isn’t. One could see this as “guilt by association,” but only if you want to narrow your understanding of desire. Hide/Seek is as much about art as it is about artists, and one of the greatest points the show makes is that “straight” artists can, and often do, create works that queer people find reflect their own desires.

Grant Wood, Arnold Comes of Age, 1930

This happens again in Grant Wood’s Arnold Comes of Age, a painting from 1930 of a slight young man staring into the distance against a fall landscape. In any other exhibition the image might be understood as one of Wood’s signature depictions of traditional America, were it not for the nude boys bathing in the corner of the portrait. In Hide/Seek the image takes on a narrative that embraces, rather than represses the possibility of same-sex desire. Additionally, the exhibition positions this desire as part of an entirely healthy personality, a welcome contrast to the many ways American culture has constructed the image of queers as morally broken and psychologically ill.

Annie Leibovitz, Ellen DeGeneres, Kauai, Hawai, 1998

This exhibition has the possibility of changing the way one views everything else in the museum, from the Elvis at 21 exhibition around the corner, to The Struggle For Justice exhibition, not coincidentally next door, which highlights people who played an important role in the history of American civil rights. Hide/Seek holds the potential to queer everything, from the Norman Rockwell show downstairs, to exhibitions at other museums on The Mall, and institutions beyond the Nation’s Capital.

©2024 Tucker Neel. All rights reserved.